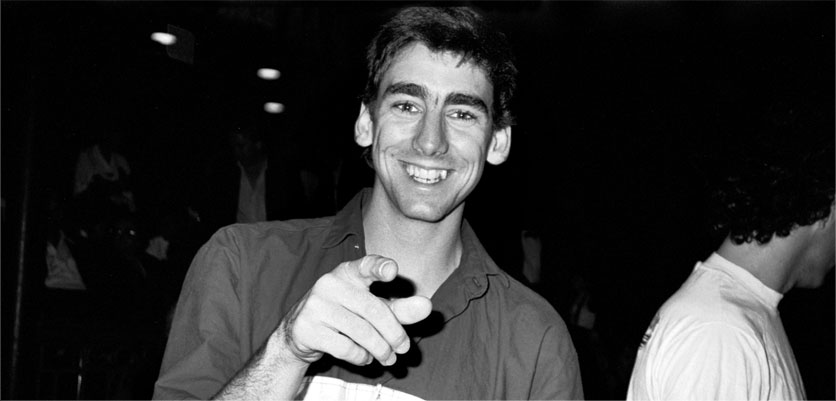

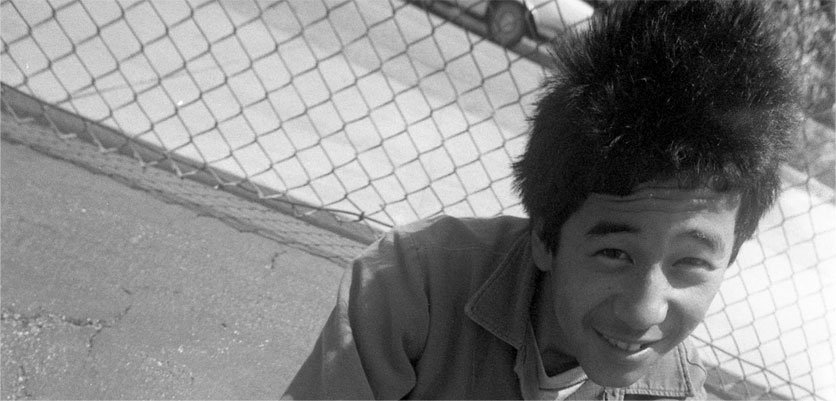

Lance Mountain

Lance joined the Bones Brigade in 1984, and was the only Brigade member to have come from another team (Variflex) as an established Pro.

Soon after joining the Brigade, Lance won the Upland Combi-Pool contest and then the Tahoe contest with his board literally ablaze. When Stacy began filming the Bones Brigade Video Show, Lance became the go to video guy because he lived in Los Angeles and was willing to be the comedian. The video was based on a day in the life of Lance Mountain and his skillful and comedic skating greatly increased his visibility and popularity after the video was released.

Lance's combination of video visibility and contest successes created enough popular demand to earn him a pro model with Powell-Peralta much sooner than expected. He eventually became one of the most popular skaters on the team based on his ability to make difficult maneuvers look easy and accessible to all.

As Powell-Peralta began to develop a deck graphic for Lance, he was offered a VCJ kull & knee bone-based theme playing off the other skull and dragon inspired Brigade decks, but he wanted something different. Company artist, Vernon Courtlandt Johnson (VCJ), was also working on concepts of cave painting figures for the second Brigade video Future Primitive, and Lance asked to go in this direction instead, which explains where his outlier graphic came from.

Known as the funny guy of the Bones Brigade, Lance had the confidence, charisma and ability to demonstrate the true essence of skateboarding -- fun and universal accessibility.

He is still ripping today, and is one of the most respected skateboarders in the world, regularly placing in the top tier of today's multi-generational Masters' Contests.

Lance is sponsored by Flip Skateboards, Spitfire Wheels, Nike skate shoes, Independent Trucks, and Bones Bearings. He is married, & has one grown son.

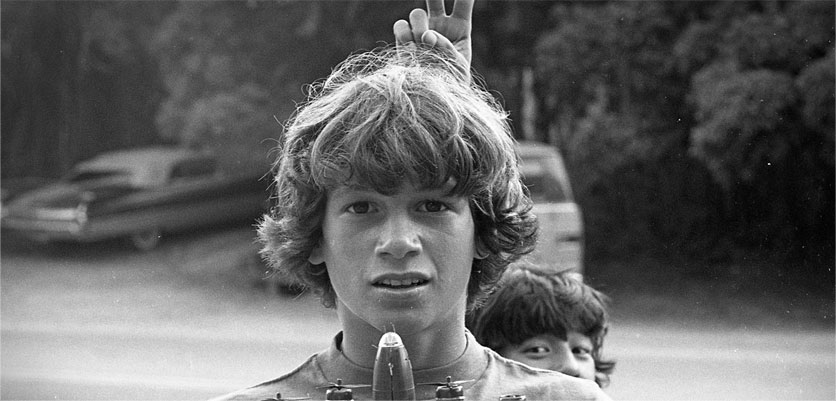

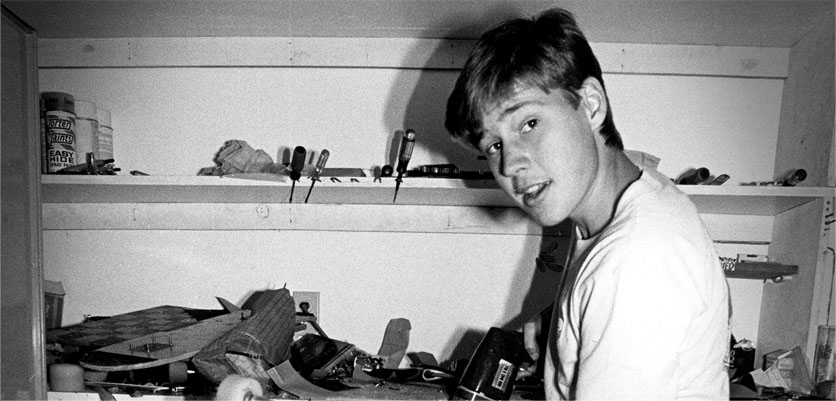

Mike McGill

Mike McGill grew up in Florida, and journeyed to California in 1978 with his buddy Alan Gelfand, who was sponsored by Powell-Peralta. Stacy Peralta flowed Mike some product, and a magazine photographer captured an image of McGill at Marina Del Rey skatepark, which was later picked to be the centerfold in Skateboarder Magazine. By the time that issue hit the streets, Mike was offered an official spot on the Bones Brigade.

McGill is best known for his invention of the McTwist (a 540° air), which he learned while teaching skateboarding at a Swedish summer camp in 1984. When he returned to the US, he officially unveiled The Trick at the Del Mar skatepark contest in August of that year. The McTwist was a ground-breaking maneuver which took skateboarding to new heights and became essential to winning vert contests in the mid 80s.

Mike's first graphic was a fighter jet, which harmonized with his friend Alan Gelfand's army tank ollie graphic. The Skull & Snake design was Mike's 2nd deck graphic with Powell-Peralta and was chosen to resonate with Ray Rodriguez's successful Skull and Sword graphic. The lightning crown and snake were included after a discussion between Mike and artist Vernon Courtlandt Johnson (VCJ) to represent Floridian elements. This board was initially released in 1984 and went through several iterations to become one of skateboarding's most iconic graphics.

Mike is still ripping and placing in masters division contests. He owns Mike McGill's Skate Shop in Encinitas, CA., is married with two children and skates for Powell-Peralta.

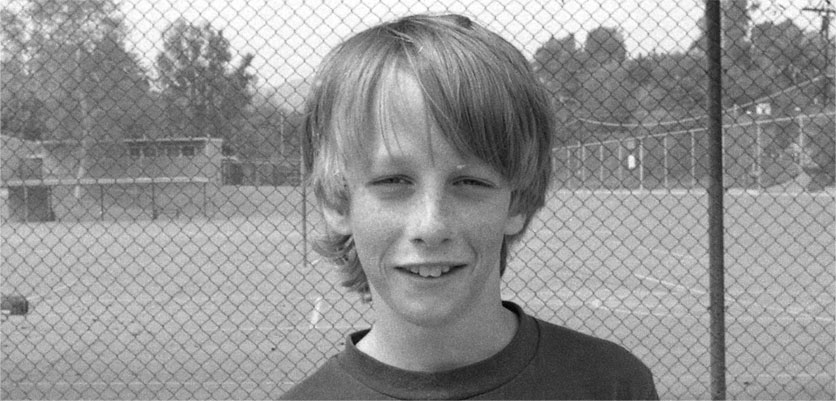

Tony Hawk

Tony grew up in the San Diego area and was a local at the Del Mar Skate Ranch. His father Frank and mother Nancy became active in promoting skateboard events to support Tony's interest in skating and encouraged him to follow his heart, instead of forcing him to pursue more traditional sports. This made sense, not just because Tony was fixated on skating, but also because he was a thin, gangly, hyperactive kid who was athletic and fiercely competitive, but awkward at the time, and his peers developed earlier than he did. Legend has it, he was so small he had to ollie into aerial maneuvers in order to attempt them.

Many older skaters made fun of the way he skated, because he was focused on learning new maneuvers instead of just stylizing maneuvers they had already perfected. Stacy saw great determination and creativity in the young Hawk, however, and asked him to join the Bones Brigade in 1980, just as skateboarding was about to enter its first slump.

Tony continued to invent new maneuvers at a breakneck pace, changing the focus of vert skating to the more technical style we're accustomed to seeing today, in the succeeding years.

When Hawk turned pro in 1982, in the very middle of skateboarding's dark ages, his first deck graphic was a soaring hawk. Although he was beginning to dominate the few contests skateboarding could muster, his deck sold poorly. The tiny market responded well to Ray Rodriguez's Skull and Sword graphic, however, so for his next deck graphic, Powell-Peralta decided to try another skull.

In 1983, Vernon Courtlandt Johnson (VCJ) illustrated a human/hawk skull over an iron cross, and as skateboarding started to rebound in 1984, it became a huge hit. Sometimes referred to as the screaming chicken skull, its one of Powell-Peralta's most iconic graphics from the 1980s.

Tony Hawk is undeniably the most recognizable name in skateboarding today, and his combined skate and video game revenues have made him the most financially successful as well. He still lives in the San Diego area, has 4 children, and runs his own skateboard company Birdhouse Skateboards. His name is also licensed to Quiksilver for clothing, Nintendo for video games, BONES for wheels, and other manufacturers of quality merchandise.

Tony is the founder of the Tony Hawk Foundation, which offers guidance and financial grants to those striving to start skate parks in low-income areas. His foundation has helped to found over 400 skate parks, and given away over 3.5 million dollars.

In 2009, Tony Hawk was inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame in Simi Valley, CA.

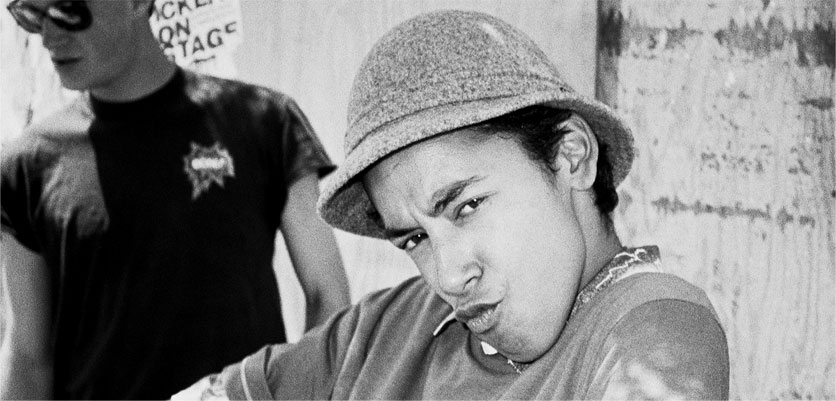

Tommy Guerrero

Tommy Guerrero grew up in San Francisco, California, where he learned to skate its hills, streets and sidewalks instead of pools and ramps. He took the flatland ollie pioneered by Rodney Mullen and extended it by ollieing over the obstacles that line its hilly streets, as he carved three dimensional lines down the streets of San Francisco.

Skateboarding was looking for a new direction that would enable its millions of new devotees to feel part of the skate culture they saw in Powell-Peralta's videos. It needed to have an accessible terrain and to be not so advanced in skill level that it would deter those new to skateboarding. The time was right and the skate paradigm began to shift from vertical skating to street skating, and Tommy was there with the goods at the forefront of skating's new direction.

When Thrasher Magazine recognized the shift in the direction of skating, it sponsored the first Street Skating Contest, and Tommy won it. This contest and those that followed, created a new resonance and excitement that changed the industry once again, and demanded new Pros and new companies to represent this new street skating direction.

Tommy was a true pioneer of street skating and epitomized the modern street skater. Even though he was not as experienced as more senior members of the Brigade, it was time for him to turn pro and to get his own pro model deck. The new market created by the senior Brigade members was demanding it. Thus, Guerrero was one of the first to have a pro street model.

In 1986, based loosely on a car hood decoration, Kevin Ancell created a V-8 "Dagger" for Tommy with a border of chrome and roses, wrapping the rails of the deck for a lowrider feel. Tommy's deck was successful, and so for his second model, this concept was updated by Vernon Courtlandt johnson (VCJ) to the more widely known version of the Flaming Hot Rod Dagger reproduced here. Tommy's pro model became widely popular as street skating took off, displacing vert skating altogether in the late 80s.

By the early 1990s, street skating was the new center of skating and Tommy and Jim Theibaud (another Powell-Peralta amateur) left The Bones Brigade to form Real Skateboards and Deluxe Distribution, which they still operate successfully to this day.

Tommy is also known as a talented musician and guitarist, gaining recognition from Rolling Stone Magazine, and producing 7 albums and a number of acclaimed singles. Tommy also plays with a group called Blktop Project that includes Chuck Treece and Ray Barbee. Tommy Guerrero still lives in the Bay Area and has one child.

Steve Caballero

Steve Caballero hails from San Jose, California and joined the Bones Brigade in 1979, after being discovered by Stacy Peralta at a contest held at Winchester skatepark. Steve turned pro in 1980 and was voted Rookie of the Year. During the finals at a skateboard contest in Upland, CA, Steve unveiled his signature maneuver, the Caballerial, a 360° ollie air above the coping of a pool or ramp. CAB ruled the contest circuit for several years after this, inspiring many of the Bones Brigade's present and future members to innovate their own tricks.

CAB's first Powell-Peralta pro model featured a dragon illustrated by Vernon Courtlandt Johnson (VCJ) and inspired by a concept sketch provided by Steve himself, perhaps foreshadowing his recent success in the art world, where he has participated in a number of art shows with his original paintings.

Steve has followed skating's many turns and changes flexibly enough to reinvent himself over and over during his 35 year career. No one in the industry has been as successful over this long a period or has remained with his original team sponsor. He has been with Powell-Peralta since 1979, making Steve the most loyal professional skateboarder of all time. In addition to being one of skateboarding's most famous practitioners, Steve has also had careers as: a rock musician, appearing with The Faction band; a skate photographer, being published in skate magazines; a painter, currently displaying his paintings at art shows several times a year; a motocross rider, recently sponsored by Honda; a collector of pop cultural items over the years; a devout Christian, testifying with fellow skaters and friends; and a husband and father, mentoring his three children.

2012 marks the 20th anniversary of his Vans signature pro model The Half Cab. It is considered to be one of the most copied and longest lasting shoe designs in skateboarding. Steve was also one of the first skaters to be sponsored by a shoe manufacturer, pioneering a formula for financial success that continues to this day.

CAB continues to skate, compete and win masters division skate contests around the world, to play music with his friends, and generate paintings for his art fans. Steve has many pro models with Powell-Peralta Skateboards and continues to live in the San Jose, CA, area with his wife Rachael. Steve is sponsored by Powell-Peralta, VANS, Independent Trucks, Bones Bearings, and Jimmy'z.

In 2010, Steve Caballero was inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame in Simi Valley, California.

Rodney Mullen

Rodney grew up in Florida, where he learned to skateboard at 10 years old. As he progressed, he became completely obsessed with skating, and developed a ground breaking string of new freestyle oriented tricks, completely by himself. This caught the eye of Tim Scroggs, one of the earliest Bones Brigade members, who was also from Florida. Tim got Stacy Peralta, his team manager and mentor, to watch Rodney, which immediately got him on the amateur team in 1980.

Again at the urging of Tim Scroggs, Stacy and George flew Rodney to California for the next big freestyle contest in Oceanside, where he defeated Steve Rocco to take first place. In the next 10 years, he was only beaten once. Rodney attributes much of his originality to being isolated on his family's farm, which allowed him to completely focus on developing new tricks in the privacy of his own practice area and without any influence from his competitors. When he went to competitions, he would drop these new tricks, obliterating his competition.

As the first skater to adapt Alan Gelfand's ollie air to the flatland, Rodney Mullen is the godfather of modern street skating. Rodney's flatland ollie was years ahead of the industry and sport, and so he proceeded to just use this new lever to move the entire skate world into the third dimension. It took nearly seven years for skaters to begin to apply his flatland ollie to the streets and use it to ollie up onto objects and back down again, but as that happened, street skating was born, changing skateboarding forever.

Although freestyle was not a widely popular skating style, his incredible creativity and contest prowess demanded that he have his own pro freestyle deck. Rodney's nickname in Florida was Mutt, which lead to his first pro deck graphic of a robotic dog. For his second pro model, the company decided to go with their popular skull and bones theme. In 1986, Vernon Courtlandt Johnson (VCJ) illustrated a skeleton freestyling on a chessboard, twirling a crown in recognition of his amazing winning streak. This successful design lasted until 1989 and would be the final Mullen model produced by Powell-Peralta.

The street style revolution created opportunities for many smaller companies to focus on this new skate paradigm. Sensing this, Rodney left Powell-Peralta to co-found World Industries with Steve Rocco in 1990. A decade later he and Steve sold their company for a handsome profit.

In 2000, Rodney Mullen founded and designed Tensor Trucks. He is a Pro for Almost Skateboards, has a Pro wheel with BONES wheels, still skates almost daily, continues to develop new tricks.

Stacy Peralta

In 1977, Stacy Peralta was a 20-year-old champion skateboarder with the world's best-selling skateboard model. Renowned as the smoothest pro around, he starred in movies and travelled the world as an ambassador for skateboarding. Unfortunately, accomplishments like this mutated hideously when transferring outside the skateboard bubble and an adult dedicating himself to a kiddie fad made him snicker bait for non-skating peers.

"Skateboarding was considered as trivial as the pogo-stick," Stacy says. "I sometimes think how remarkable my parents were because if my son spent the greater part of his day riding a pogo-stick, I'd worry about him."

The fact that Stacy cashed monthly checks in excess of five Gs may have shifted his parent's perspective, but he soon put a stop to that. A typical 1970's-era professional skater career mimicked fireworks: blast up, blow up and fall down sputtering out. Naturally, most pros rode that ride as long as possible, but Stacy quit Gordon & Smith skateboards at his peak and partnered up with engineer George Powell to start their own brand Powell Peralta in 1978. No other pro had pulled the e-brake on his own career and it confused fans to no end. Not wanting to overshadow the young team he recruited, Stacy refused to issue himself a pro model on Powell Peralta but still won SkateBoarder magazine's skater of the year in 1979. Officially retired, Stacy surprised himself by enjoying nurturing his team even more than his own pro career. And he kicked ass at it. Stacy had an unparalleled instinct for finding hidden talent, always bypassing obvious choices to recruit raw and "weird" skaters based on personality rather than obvious physical talent. Steve Caballero was picked after placing fifth in a contest. After bailing a trick, Tony Hawk's face full of self-disgust caught Stacy's attention. He recognized Rodney Mullen's technical precision stemmed from a desire to control something in his emotional harrowing life.

By 1983, Stacy had picked a team that dominated contests and created entirely new ways of skating. Unhappy with the way the magazines covered the Brigade, Stacy and cohort Craig Stecyk III circumvented them with newfangled VCRs and created a new propaganda weapon. After firing the non-skater he'd hired to direct, Stacy gave himself on-the-job training and created what was essentially a Powell Peralta's low-fi home movie. The Bones Brigade Video Show was the first skateboard video and it instantly rearranged skate media priorities. Expecting soft sales of perhaps 300, they sold a hundred times that and boosted Powell Peralta's market share in the process. Future Primitive: Bones Brigade Video 2, released in 1985, is often argued as the "best" skateboard video ever produced. Unlike BBVS's simple linear storyline and collection of tricks, Primitive marinated itself in skating subculture. Skaters crawl out of sewers, skate back alleys and decrepit ditches. Primitive pointedly turned away from the mainstream. Gone were the days of longing to be accepted and the Brigade reveled in skating's anointed position as cockroaches of traditional sports as they skated an apocalyptic landscape.

Stacy directed a steady string of successful videos, peaking in 1987 with the beloved cheese fest The Search for Animal Chin, an ambitious story of the Brigade's search for the elusive Chin. (Think 1970s-era porno with skating instead of sex. The acting quality was pretty much the same though.) Skating bombed out three years later and Powell Peralta crashed and burned. Stacy had held together skateboarding's most successful team for a decade—dog years in skateboard terms. The team's influence regarding contest domination, progressive tricks, marketing has never been matched. After leaving Powell Peralta, Stacy pursued his filmmaking aspirations, eventually writing feature film screenplays and becoming an award-winning director.

George Powell

The first time George Powell saw a skateboard it wasn't called a skateboard. "I saw somebody riding a two-by-four near the beach and went home and built one for myself," George says. In the mid-1950s there were no commercially available skateboards but the OG generation lit the fuse with DIY projects involving scrap lumber and mutilated rollerskates.

A decade later, George was married and studying engineering at Stanford. He hadn't rolled in years, but cashed in his books of blue chip stamps for two commercially produced skateboards. He and his wife eventually burned out on rolling around the campus and mothballed the boards.

A decade after that, George passed down his skateboard to his son, who promptly complained that his relic ride sucked compared to newer models with urethane wheels. Ever the tinkering scientist, George researched the new material and composite decks and set up a low-rent R&D lab in his garage and began baking prototype wheels in his kitchen oven. His day job revolved around the aerospace industry and he employed its high-tech approach to making aluminum skinned decks and the first double-radial wheels called "Bones" due to their rare white color.

George ran Powell Skateboards with moderate success until one of the most famous skaters of the era randomly rang him up in 1978. Stacy Peralta and George had spoken a few times before and the skater had always been impressed with Powell's product. The engineer likewise appreciated the marketing power that the star skater provided. "I was a designer—I didn't know many skaters," George says. They formed Powell Peralta and each owned their own side of the company coin. Stacy and his creative cohort Craig Stecyk tackled marketing, quickly producing artistic and sardonic ads unlike anything seen in skateboarding. George hunkered down and focused on improving skate product. Powell Peralta found their stride at exactly the wrong moment. "Stacy had just introduced the Bones Brigade concept," George says, "we had really high-quality wheels and decks and then the market just died. Went to zero. We'd call shops for orders and they'd say they were going out of business."

Powell Peralta weathered the depression until a new generation discovered skateboarding in the mid-'80s. Sales peaked in 1987 with annual sales topping 27 million bucks, but by the end of the decade the landscape had changed and the iconic company absorbed multiple near-fatal wounds. Stacy and most of the Bones Brigade departed, but George retooled his business and brought his companies back from bankruptcy by returning to his original focus on upgrading standard skateboard components. Today, Bones Bearings and BONES wheels are among the strongest and most respected brands in skateboarding.

Lance Mountain Interview

QUESTION: Do you recall the initial conversation you had with Stacy about doing a Bones Brigade documentary? LANCE MOUNTAIN: When the Dogtown and Z Boys documentary came out, I remember asking Stacy, “What next? Are people asking you to do the next one about The Bones Brigade?” He said people were already mentioning it to him and he was like, "No way! I’m not doing that." That was around ten years ago.

A lot of people were asking me when were they going to do a documentary on the 1980s, the era when I became popular. I understood why: The numbers of us who grew up idolizing Alva in the 1970s was in the hundreds of thousands but it was in the millions for the 1980s, so a lot more people were asking me about doing a film on the Bones Brigade.

You played a catalyst in getting the film rolling, right? LM: I just felt that it would be good and what people wanted. The main guys in the Brigade have moved on and had great lives after the Powell Peralta broke up, but there was something about that time that was special to skateboarding. We didn’t need to revisit it. Skateboarding has only grown better for all of us involved.

Skateboarding has missed a bit of what made the Bones Brigade special and that was all the necessary pieces being together and there’s something to celebrate in that. I’m not sure that can be done again. Skateboarding has developed so much that it’s probably not possible, so I think that story is good for skateboarding as a whole.

Skateboarding has so many nuances and unwritten codes. Do you think anybody who wasn’t there could tell that story? LM: No. Naw, naw, naw—it’s our story. Not to bash anything, but it’s like the difference between the documentary on Dogtown and the movie about Dogtown. They thought that real story wasn’t interesting enough so they made some changes, made certain parts more accessible to non-skaters.

It’s all about telling a story and who does that best and who has the best, most complete package to tell that story. It was the same back in the 1980s. This film doesn’t say that other people or companies weren’t contributing or doing innovative things but they didn’t tell the story as well as Powell Peralta. Other teams and skaters were great, but their package or their storytellers were not as talented. The Bones Brigade had the best package for telling the story of that era. Stacy and Stecyk were the storytellers—they explained the story to skaters in the 1980s so why wouldn’t you choose Stacy to tell the story now? He knows how to tell the story about skateboarding. Why would you go outside of that?

Skateboarding has always been a do-it-yourself activity or art form. You might be able to bring a documentarian who’ll make a technically better documentary, but they won’t capture the spirit or the feeling of what skateboarding about. They’ll just be documenting the facts and skateboarding has nothing to do with facts. It has to do with emotion and feeling and art and passion … it’s just not facts. Skateboarding has never only been about being good only—it’s about capturing someone’s passion, making them love it. Skateboarding is theater. Nobody can document skateboarding better than a skateboarder.

Was it important for you to have this film made? LM: Yeah, because in some sense the chapter was never finished. It ended lame. It ended wrong. It ended sad. It didn’t need to end that way. But, if it hadn’t ended, each of us would never have gotten to the places where we are now.

This film is important for skateboarding because history can change what’s going on now. Skateboarding history hasn’t always been available because the coverage, the articles written, were being done to market a brand. Whatever had happened was being covered up and written over to try and sell a product for tomorrow. For the longest time, skateboarding wasn’t based on what had happened, it was about what was going to happen. One of the reasons that this movie could even happen is because Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Steve Caballero and myself were the first skaters ever to have product on the market from the beginning of the ’80s and we never left. Every other pro has had product for five years, ten years, dropped off, maybe come back decades later. This film isn’t just a look back on the glory days—we’re still doing it. Now that a modern pro has a longer career, they’re looking to us to figure out how to keep a career going for a long time. It’s much harder for a kid starting out on a skateboard today to have a goal to do something creative, innovative, progressive—or just for fun their own way because circumstances and culture teach them the goal is to be famous.

This film shows that for anything to be of a certain value, have impact over time, it takes people being very passionate and working together combining different sets of skills. Not one of the participants on their own can overshadow the others and take whole credit for this being a thing of value. That’s the story: teamwork and perseverance. It’s just inspiring to skaters and non-skaters alike.

Tony Hawk Interview

QUESTION: What were you thoughts upon hearing that the BONES BRIGADE: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY was going to be made? TONY HAWK: I was excited. I knew it was going to happen eventually, but I was more relieved that Stacy [Peralta] was directing it because anyone else’s version wouldn’t be from an inside perspective. I know Stacy is one of the best documentarians and when you combine that with the fact that he was there the whole time, it’s obvious that he was the best choice.

What was your reaction after seeing the first screening? TH: I was surprised at how emotional it was. It seemed like it was going to be more of a celebration of our time, not anything so deeply emotional and personal. I had a sense of it during the interview, but I had no idea how deep everyone else would go. I thought I exposed as much as I could and felt vulnerable because of it, but then I saw the other guys and realized that I didn’t even get started. After seeing it, I think we all feel a bit more vulnerable and exposed as to what the days of the Bones Brigade meant to us. I think Stacy is the only one who would have gotten it out of us. We just didn’t trust anyone with our story.

Many TV shows have produced segments about your lifehow does this film differ from them? TH: This film is more about the psychology of what we did and why we even started trying to do it while those other TV shows highlights the accomplishments. This time we’re really talking about what drew us into doing something so different.

What did you think of the segment on the magazine manufactured rivalry between you and Christian Hosoi? TH: I was happy to explain it after having lived through it. I wasn’t emotionally tied to it so it was pretty easy. I liked how it put it in a new light because a lot of people misperceived it as Christian and I being enemies. We weren’t enemieswe were the top competitors who, by default, were pitted against each other in the eyes of the public. In reality, we were just having a blast being young and successful.

During the 1980s, that success rarely transcended the skateboard bubble. In the film, there’s a clip from an Italian TV show featuring you and Lance. Can you lay out the backstory to give people a sense of how you were regarded by the mainstream back then? TH: We were brought to Italy to perform on a TV show and were basically considered strange circus freaks. There was a Roller Boogie crew, a guy that juggled chainsaws, the hacky sack champions and us, as skaters. They built a ramp on stage and we explained that the ramp wasn’t solid enough. Through various language barriers they told us that we’d never break this ramp. On one of my first runs, I knee slid and my knee went through the ramp. Then they tried to dress us in what amounted to painted cellophane shorts. During our practice session, my board shot off the ramp into the audience seats. They thought it was too dangerous so they taped our segment and showed it to the audience during the show. Lance and I then snuck into the audience so we were spectators to our own "demo."

The Brigade went through a lot of strange times together, did that create a unique bond between you guys? TH: Absolutely. We have a strong connection that we’ll always have because we did go through so much at a young age and within a short time frame. We knew we were part of something special at the time, but I dont think we realized the resonance it would have and how formative it would be for people of the same age or interest levels. We were happy to be liked, but didn’t recognize that we were inspiring people to follow their dreams. Some people saw us as examples of doing what you love despite the status quo.

Many skaters have a limited sense of the history. Do you think this film shows cultural aspects that are difficult to convey to younger skaters? TH: I think it’ll help enlighten kids nowadays as to what their roots are. Some of them make a lot of false assumptions about how we started skating and how we became successful. They just assume that it was always the way that it is now and you always had the opportunity to be successful and make a career out of skateboarding. None of that existed. I think we helped create that.

Has this documentary experience brought you guys closer? TH: It’s definitely been a catalyst for us to start working together again because we want to help promote the film, but also assess each other’s interest levels in doing reissues and how far we want to take this nostalgia. It’s definitely made us question if we want to live in this nostalgia or be known for who we are now and that’s a fine line to walk. It’s been an ongoing conversation with all of us. The bottom line is that we want to approach this as a group with a common goal.

Unfortunately, the group will be minus you in Sundance. TH: When Stacy told me the screening dates I was disappointed because I’d already committed to a tour in Australia. Had I known about Sundance earlier, I would have made it work, but it was too late: I was contractually locked in. I have a few days off during the tour and did try to figure out how to fly back for one of the screening, but it’s physically impossible.

Even though youre spectacularly successful, do you still feel like that scrawny skate rat kid obsessed with something dismissed by most people? TH: I don’t think my success has changed my outlook on skating. If anything, it gave me a chance to skate more the way I always wanted to. For a long time, I didn’t want to compete and I wanted to be more flexible in terms of my opportunities. During the ’80s, if you weren’t competing as a professional skateboarder, you couldn’t make a living. That was the bottom line. But once it hit in this bigger way, I was able to create a new path for myself where I could still skate actively, be progressive and be recognized without competing. If anything, this success has allowed me to pursue my dreams on my own terms.

You pioneered new opportunities for professional skatersare you still expanding those boundaries? TH: Yeah. I’m still making it up as I go along. In a lot of ways, I’m one of the guinea pigs of how far can you take this and at what age do you cease being effective or progressive. I’m still trying tricks. I’ve spent the last two days trying to get a new trick on video and I’m going to go out next week and do the same exact thing until I get it.

Rodney Mullen Interview

QUESTION: Stacy mentioned that you had some heavy reservations about participating in a film that delves so heavily into your past. RODNEY MULLEN: I did and there were a couple of levels to that reservation. Literally the day Stacy called me, I was coming off an interview that I stopped midway. I walked away because that specific interview wanted to praise and contextualize what we did in the past at the expense of what we're doing in the present in a very backhanded way. You can easily fall into that [way of thinking], even unintentionally.

The skateboard community as it is today and that sense of belonging—this is it for me. These are things that matter most to me. I understand that yesterday and that past is sewn into the fabric of today and it's not isolated as something different or better or more pure because there was less money. There's a natural tendency to associate the past with being more pure and having more soul. I had a very strong reservation about participating because I want very much to live in the present.

And also because of the way the Bones Brigade dissolved and how afterwards the industry went into a freefall … I didn't want the emotions of that time to contaminate the perspective of the documentary and that could clearly happen.

I voiced these concerns upfront and Stacy gave a long pause, not because he needed to deliberate but to give these concerns their space. Then he said, "I will guarantee that this will not happen." And he made sure of that throughout.

The other part is that so much of my motivation and what I was dealing with [in the 1980s] comes from a very private home life. Skating was an outlet from home life and it's very much what made me, me. That was my biggest struggle. I can't describe who I was or what I was going through without digging up a lot of that stuff. I didn't want the documentary to be about that or have a lot of footage of me saying things that didn't reflect well on how I grew up. I was very sensitive to that and Stacy could not have been more respectful and supportive.

You were the last of the Brigade to commit to this film. Why did it take so long time to feel secure? RM: Projects like this are never one person's property. They just aren't. They go the way they go. It's a documentary, not fiction. Stacy was very clear and he gave me his word and I believed him—again, this is not a reflection of me doubting Stacy one iota—but the reality is that these things have a mind of their own. People say what they say on camera and it gets put together and it goes where it goes because a documentarian is after truth—he's not after a predisposed story.

A month had past and it was enough time for an interview to come out and it raised flags [about the film] that were very much beyond Stacy's control. I was already trigger-happy and I started shooting, in a sense. I called Tony to basically tell him that I was going to pull out of the documentary. I was so worked up by my own fears. Tony happened to be in Dubai and we talked for a long time. Tony just said, "Look, I'm in and the story needs to be told with you … maybe Lance could speak for you or I could speak for you, but we need you." He talked sense to me and that recommitted me.

So the camaraderie you guys shared 25 years ago while in the Brigade came full circle. RM: That's right. Anyone else could have said what Tony said and I would have taken it with a grain of salt and thought, That's fine, but my life is pretty good now without the documentary and nothing is worth jeopardizing what I have. Thanks for your advice, but I'm out. I feel such a connection with Tony and there's a bond of respect.

How did you feel that Stacy was also the one preparing the questions and doing the interview with you? RM: That made all the difference. Stacy is very respected in the film world for a reason. One of his gifts is the ability to lock in on whatever you're feeling. He locks in on who you are and allows you to just go with it. He asked me a few things at the beginning and the way he posed the questions had a certain direction and I took another direction and kept going and he just went with it. That's what made it so open and free. I don't know who else I could have opened up with.

During the 1980s, skateboarding was self-contained and survived by relying on an instinctual DIY ethos. Did this documentary feel like the natural way to cover that era and cultural impact of the Brigade? RM: Yes. You've got to connect with the person next to you. The team is very much a representation of what you�re about, not just what you can do. We were all very selective about who was to be let in and it didn't matter if they were articulate, it was a question of does this guy feel right? When we formally began and had a meeting at LAX, we had that discussion and Stacy asked, "Who do you feel comfortable letting in?"

What were your initial thoughts upon seeing the first screening? RM: Sit still and don't run. I had already done the interviews and I knew what I said and I let a lot of my heart out. I had to come to terms with [the fact that] some people may think that the heaviness is all that I'm about. When I saw the other guys opening up and how it was woven together … I didn't question much at that first screening.

Immediately, I was engaged with the feel of the movie and its authenticity. There were lots of times I thought, I never knew that about this person. Naturally, I cringed and flinched when I saw and heard myself, but by the time it was over I was just dizzy. My thoughts were so loud that I didn't know what was going to come out of my mouth because I was so overwhelmed emotionally. I had to physically put my hand over my mouth because I didn't know what I was going to say. But I felt good inside.

Interview with Director Stacy Peralta

What was the most unexpected aspect of directing this film? STACY PERALTA: How emotional it made me. Being the person asking the questions, i.e. the interviewer, got me very involved with each of the characters while shooting and all of them brought so much material to the project that it really knocked me out. Lance [Mountain] broke down in his interview, which made me break down. And Rodney [Mullen] was so emotional during his entire interview … I hadn't expected that and it had a profound effect on me.

During the 1980s, the guys and I shared moments of high elation and triumph together. Whenever I said good-bye to them at the airport, it was always sort of emotional because we were coming from such a rich experience, but I'd never had anything like this where it was so condensed and concentrated in such a short period of time. The interviews were conducted during one week, about six people per day, which is a very heavy schedule.

You started with different expectations about what kind of film you were making? SP: Yeah, I had low expectations. Seriously. I was going to cut this film myself. I was looking to work on a little film that I could do on my own time. It wasn't until we began shooting that I realized we had something very unique and I could not make the film alone. I needed to bring in somebody who knows how to tell stories. That's why I brought in the editor Josh Altman. I really needed a partner on this film. He was the perfect person because he has a terrific sense of storytelling and a great understanding of how to connect the emotion of the story.

I was too close to the material and quite a few times during post-production I told Josh, "I don’t really know what to do with this part of the film—you have to take over here. I’m just too close to it." I had so much trust in Josh. He had such a good feel for the material and characters.

What were the origins of this doc? How far back had you been planning it? SP: Around 2002 or 2003, Hawk, Cab, McGill, Lance and Tommy asked me to dinner at the LAX airport. They wanted to meet with me to talk about the possibility of a “Bones Brigade” documentary and if I would consider directing it. At that time, I was coming off of the success of Dogtown and Z Boys and didn't feel right about jumping into this field again, especially with a film where I was once again a character within the story. I felt it was too risky—way too risky. I was afraid of being looked upon as a narcissistic filmmaker. This is not to say that I didn’t feel the Bones Brigade was a viable history and potential good story.

Over the years, one of the guys would reach out to remind me of it, but nothing happened until late last year when Lance called again and said something that tipped me over: “We're now older than you and Alva were when you made Dogtown.” That line made me realize now was the time.

I talked to my wife at great length about the project. She knew my fears and reservations about the project and came up with the idea of calling the film "an autobiography." She figured that if anyone had any issues with me as the filmmaker or the guys making their own film in a sense, then telling them upfront should set it straight. The film is a collective autobiography. It's us telling our own story and we state that under the title of the film.

From a purely physical perspective, how did the documentary evolve? SP: First thing I did was put the music soundtrack together. I do this with most of my films. I need to hear what the film sounds like, what it feels like and its emotional tenor. Once I assembled a couple of hundred pieces of music, I then began reaching out to photographers, asking them to send me their images from that era. I went through the Powell Peralta archives, which represents thousands of photos, and I looked through all the skate videos I made, including hours and hours of outtakes.

I was in shock going through the old footage, especially with what Rodney and Tony were doing in the early '80s. Even though I filmed this footage myself and was there to see these tricks being introduced, it was like seeing them for the first time. They were so ahead of their time. They were laying down the tracks for future generations. And it wasn't just one or two innovations—they invented books of maneuvers. Rodney is like Chopin where he invented the studies. Both Tony and Rodney invented an entirely new vocabulary of maneuvers in skateboarding.

I put together questions as I sorted through the photos and videos. Hundreds of questions. I wrote questions for around 45 different individuals. I had to have totally different questions for Lance Mountain than I had for Tony Hawk and totally different questions for Duane Peters than I had for Craig Stecyk. It took me months to assemble these questions per each individual, subject, year, etc. It's the questions that generate the answers, which generate the narrative of the film.

Did you structure the film beforehand and paint clear bulls-eyes on certain subjects? SP: As I put together the questions for each guy on the Brigade, I searched for the problems each of them may have faced during that time we were all together. What emerged was that Rodney's father was a huge obstacle physically, psychologically and emotionally for him. Tony had an issue being accepted by people—he was spat on by skate punks back in the day and called a circus skater and many people in the skate world had issues with his father. Lance expressed huge insecurities about measuring up to the other guys on the Brigade and his interview ended up being rich with great material. On the other hand, Caballero didn't have that many issues and I struggled with him to find some. He kept saying that he went with the flow of his career and didn't fight it. He didn't have a lot of drama in his career, same with McGill.

Did you realize early on that you'd have to convey the evolution of skating's disenfranchised culture for everything to make sense? SP: That's why we tried to show that skating went out of business in the early '80s. SkateBoarder magazine died. The sport died. Arena contests died. Skateparks died. The kids who wanted to keep doing it had to build backyard ramps and we decided to take skateboarding in our own hands and have professional contests in kids' backyards. At the time, none of us knew if skateboarding would ever come back or if it was gone forever.

You and the core members of the Brigade shared a bond unlike any other in skateboarding. You were their boss, mentor and something of a father figure. How did that position affect how you made the movie? SP: It gave me an insight into the story. I knew the inner workings. I was there when Tony got spat on. I was there when Rodney suffered from what his father did to him. I was there when the tricks were introduced. It was a very unusual tightrope for me as a filmmaker and participant. Again, this was the reason I needed a skilled editor like Josh. He was very helpful in giving me the confidence to tell this story.

Did you hesitate talking to the guys about painful issues? SP: Not really. The one thing that really moves me is that we can do a project like this and interact as if no time has passed. My relationship with these guys is so different from the Dogtown guys where a lot of ego was involved. A handful of the Dogtown guys didn't get what they wanted out of their skate careers, but everyone in the Brigade got what they wanted. They got broken up and took the bruises, but kept going until they got what they wanted. As a result there were no scores to settle or festering issues with one another to resolve. When it was over, we all walked away as friends, realizing what an amazing experience we had together.

Did you schedule the interviews in a certain order or just let the skaters dictate when they were available? SP: I purposely scheduled the secondary interviewees towards the end of the week and the primary characters up front. I had Sean Mortimer come in first because I knew he'd give the general overview of the Bones Brigade experience. I started with Sean so that my crew could understand the film we were making. Sean was the first person on the first day and Rodney was the last person on that day because I knew Rodney had the potential to blow the crew away with his emotional, psychology and articulation of his experience. It's very important to me that my crew understand the film we're making, that they get onboard and spiritually bond with it. I don’t mean spiritual in a religious way, I mean that they connect with it and that's exactly what happened by properly sequencing the interviewees.

At the end of the first day, the crew was absolutely stunned by what they'd heard. I really wanted them to think, I can't wait to come to work tomorrow. When that happens, the crew comes to work excited and creates a vibe that is tangible to people walking onto the set. The interviewees come in and feel that something special is going on. It makes a difference. Duane Peters came in and knocked his interview out of the park. Glen Friedman was amazing—everybody in the film gave amazing interviews.

There was an actress working on the film as a digitizer and she wrote a letter to a friend in England saying how much they both had to change their lives after hearing these skateboarders talk about the artistic process.

Even though there's lots of serious subject matter, the film is peppered with self-deprecation and the guys busting each other's balls. "Freak" is used as a compliment. And you really stick it in and break it off with your dorky early footage. SP: One thing I learned from Dogtown was that I didn't want this to be us patting ourselves on the back. I was hyper aware of that. But, if you look back, the Bones Brigade was hands down the most successful skateboard team of all time and so how do we say that … without saying it, you know?

I felt there was potentially funny material from my career in the '70s and when I saw that goofy footage, I let Josh run with it. Josh understood how to take that material and cut it into the film in a way that makes those shots contextual but also funny. Glen Friedman and I were talking on the phone, months before production began, and he began ripping apart The Search for Animal Chin. He just tore it to shreds and made me laugh hysterically. We flew him out and got that on film. At the first screening, when the Chin segment came on, I could hear Rodney and Tony almost throwing up from laughing so hard. That was gratifying. There is a certain comic ownership to burning oneself.

It's important to have that tonal mixture. When you have the guys tell the story about Rodney running out of the van, well, it shows that Rodney is a really unique, special guy and he's imperfect in that regard. He's extremely eccentric and he has needs. It was very, very important for me to give this film a personality that didn't resemble Dogtown in any way, either visually, physically or emotionally.

Visually, it doesn't look anything like Dogtown. Most of the skating footage was shot on videotape and you emphasize that medium's inherent defects rather than treating them as problems. Josh did an amazing job with the titles, which even have that degraded tracking line going through them. SP: Josh and I worked really hard on the graphics and titles and I think it fits with that ugly '80s video look

After the first screenings, Tony Hawk commented a few times on how unexpectedly personal the film was for him. SP: Look what Tony overcame during his early career! That says more about his character than anything else. He overcame so much adversity and that's what makes a good story.

How has the experience been with the Brigade after the film? Do you think it rekindled anything within them? SP: They feel that as a unit, they had an experience in skateboarding that nobody else had during that decade. They've all told me that at different times. But, and this is very important, they did it at a time when skateboarding wasn't accepted by the mainstream. They clearly weren't doing it for the money because in the early '80s there wasn't any money to be made in skateboarding so there was a purity of intent to it. Like Lance said, their bond is similar to guys who experienced war together because at a very young age they shared one of the most meaningful and impactful experiences of their lives. Now we have it on a piece of film that we can share.

Sundance seems almost like a tour redux for the Brigade. They used to travel the world together, stuffing themselves into budget vans and cheap hotel rooms. This time it's going to be full skate camp at a rented house with everybody crammed together. SP: It's going to be just like that! I only wish Tony could be there … he tried to find a way back from Australia but it wasn't feasible. He was actually trying to schedule flying in from Australia, attending a screening and then flying back. Tony called it "a global mission" in an email, but he couldn't make it work.

There are around 20 million skaters worldwide and many of the Brigade remain stars. How do you think skaters will react to the film? SP: I would hope that the things these six individuals say in the film are things that other skaters and athletes and artists feel but perhaps have not been able to articulate. Non-skaters who have seen the film tell me they relate to it for the same reasons. At early screenings, I had people tell me the film isn't about skateboarding—it's about family. It's about the artistic process. It's about overcoming obstacles. Everybody is taking something different from it. The goal has always been to make the film universal and transcend the skateboard audience.

Last question and this concerns the skateboarders who shredded during the '80s—will they ever be able to look at The Search for Animal Chin [The most successful skateboard video in history, released by Powell Peralta in 1987] the same way again? SP: Ha! My wife says that I've ruined it for so many middle-aged skaters and that they'll never look at Animal Chin the same way again. But another person told me that they'll actually appreciate Chin even more. I really don’t know.